New Testament Authors and One

Here are considered Paul, Mark, Matthew, Luke and John, and for comparison and contrast, the figure of Peter. Elsewhere there are specialist resurrection notes.

The world view that unites these authors is that history really was divided into Paradise at first, then the Patriarchs, then the Law and now the Gospel. They are tying one scriptural base of the first three into the one they are justifying: the freedom that comes with the Messiah who died, was buried, was resurrected, and appeared. The viewpoints are generated from the stance that Jesus was raised by God and all else fits into this. The authors use what information they had into their communities' contexts of expectations and beliefs; because the writers make their own arrangements of what order to tell his ministry, it is not possible to work out the development of Jesus' thought or strategy. Everything had its wrapping.

He was called Saul until conversion and lived from 1 to 64 CE. He was born a Jew in Greek Tarsus and died in Rome probably as a result of Nero's persecution which followed the Great Fire of that year. He followed the Pharisees and in so doing took on Christian Jews who were light about the Law. Some two years after Jesus' death he experienced a conversion on the Damascus road, about which as well as the obvious explanation of receiving an appearance there are many psychological theories relating to his self guilt and even a suggestion of electrical activity in the earth from a far off earthquake.

He was called Saul until conversion and lived from 1 to 64 CE. He was born a Jew in Greek Tarsus and died in Rome probably as a result of Nero's persecution which followed the Great Fire of that year. He followed the Pharisees and in so doing took on Christian Jews who were light about the Law. Some two years after Jesus' death he experienced a conversion on the Damascus road, about which as well as the obvious explanation of receiving an appearance there are many psychological theories relating to his self guilt and even a suggestion of electrical activity in the earth from a far off earthquake.

He does not describe himself and his own writings only hint at his background. Nevertheless Paul seems to have had a complete change as a result of his encounter experience. From being Pharasaical about the Law he became a radical organiser. His first leading evangelist or church leader was Lydia, a woman. He had expected women would be prophesying (particularly in the Corinth church). This possibly suggests that some what we would identify as anti-feminist elements in the texts were later insertions to accord with tradition. All sorts of barriers were broken, bringing in the Gentiles and the sexes; and faith was emphasised well above the Law.

Paul will have picked up the running beliefs of the new church communities and the tradition of appearances, for example their order. Into this he inserted himself at the end and added his authority. It is Paul's interpretation of faith in a situation of expectation of an end of the world and coming of the new dispensation that a definition of Christianity is established. Yet (see Peter below) the variance is at the margin, although a significant margin regarding a theological over a Hebrew Bible eschatological Christ (something emphasised in John's Gospel).

That faith was of an immediate future advent of Christ, but this declined as it did not happen, to become a kind of divine grace centred around the being of the Christ figure itself: Christ and him crucified. Paul has preaching Christ as the centre, rather than the Kingdom of God.

He was careful to state that he received the gospel (1 Corinthians 15) from the centre - Peter, James and the Apostles - and that what he preached he submitted. So he was keen to emphasise that his message was not a one man band. Some must have suspected this, and clearly he was as if semi-independent. He was defensive about his place in carrying out the mission. He emphasised that the belief of the people was coming from the fact that he and the centre preached a particular message. He was weak but God was using him and God was making achievements in the face of much denial.

The core-agreed but Pauline-emphasised message was:

- The prophecies are fulfilled

- The New Age was begun with the coming of Christ

- Christ was from the seed of David.

- He died according to the Scriptures (Hebrew ones)

- He died to end the sinful age

- He was buried

- He rose on the third day according to the Scriptures (Hebrew ones)

- He is exalted at the right hand of God

- He is Son of God

- He is Lord of the alive and dead

- He will come again

- He will be Judge and Saviour of all

Paul was controversial from the start, and remains so with those who think he distorts or invented Christianity. At the time he might have become regarded as heretical by many. Yet Luke's interpretation of him in Acts and in his letters he is a dominant voice in the New Testament.

Incidentally, Acts and the Pauline Epistles when comparable often do not work together well, such as in the visits to Jerusalem. Acts is not a biography of Paul, but a narrative that Judaism is fulfilled in Christianity and Christianity should seek out the Gentiles. Peter accepted with Paul that Jewish identification is not, in the end, necessary to be in the community despite Peter's pro-Jewish bias.

Another difference between Luke and Paul is that both could be talking about the same phenomeon of speaking in tongues and yet the writers interpret it differently. For Luke, writing much later, preaching the gospel in tongues to all nations derives from speaking the Jewish Law in many languages that the world can understand and yet only Israel follows (once again, the theological link is made back to the Hebrew Bible: Christians are the only ones following the Messiah). For Paul it is praying in a nonsense language as seen today in charismatic services.

Paul was constantly attacked, but he did carry the definition of Christianity. He had never met Jesus the man and so promotes a Christ the first of the resurrected, a spiritual body for all. Paul above all goes for the man, the event of the coming new age derives from the man, and as the event seemed likelier not happen, the man was even greater the focus. It was a huge matter and massive change for a once observant Jew and persecutor of Christians to suddenly adopt belief in the messiah and last days, and to promote it with such vigour.

It's a game of probabilities regarding the authorship of his letters.

|

Pretty certain by Paul

|

Romans

1 and 2 Corinthians

Galatians

Philemon

|

|

Most likely

|

1 Thessalonians

Philippians

|

|

Some doubt

|

Colossians

|

|

Unlikely

|

2 Thessalonians

Ephesians

|

|

Ruled out (unless scraps)

|

1 and 2 Timothy

Titus

|

Colossians, Philippians, and Philemon are prison letters. Ephesians likely came after his death and is a display of his teaching.

The point about these letters is that they are the earliest writing of the New Testament and therefore get readers as close as possible to the early communities and therefore core beliefs of the resurrection if not an explanation of what it constituted. 1 Thessalonians is probably the earliest writing and it with Galatians and Corinthians set out to keep contact with those he had already visited and responded to reports of disputes and lapses. Romans was written before his arrival there, however. He knew of communities in Rome but not personalities among its twelve or so synagogues. The history here is Claudius expelling these Jews in 50 CE, due to subversion of Chrestus, and they were able to return in 54 thanks to Nero but always on a knife edge up to 64 CE and the Great Fire.

He consistently emphasises that Christianity is more than observant Judaism. It is not about keeping the Law ever more faithfully, nor about eating meat once sacrificed to Pagan gods bought at Corinth. Again there is the breadth of who can be a Christian. He also argues against wisdom and gnosis on Greek lines. He demands a focus on the one Christ and not around leaders.

The prison letters may be from a number of prisons. The letters show who helped Paul, and Timothy is a key associate and possible accompanying prisoner who shares in the authority of the letters' shared origins (and, given the doubt, also shared 1 and 2 Thessalonians). Aristarchus and Epaphrus are described as prisoners. There is Paul's criticised associate John Mark, and Luke (but unlikely to be the author of Acts), Demas and Jesus Justus with him. Tychichus and Onesimus were likely journeying from Paul towards Archippus and Philemon in Asia Minor. Philemon is about an escaped slave called Onesimus written in a personal style. So many fell away from assisting Paul, except this Luke.

So the letters reflect the travels but illustrate far more. Then there is the biography.

Two years after his dramatic conversion Paul visited Peter and James in Jerusalem. He listed the appearances tradition (a roll call of authority) but mentioned no tomb.

He preached up to about 38 CE around the Jordan, in Syria and in Cilicia and met opposition from strict Jews who found the Christians to be heretics. Paul had set up base in Antioch where these Christian Jews were already in existence.

About 48 CE he went to Jerusalem for a second visit to discuss disputes, especially the difficulty that certain Christian Jews in Antioch insisted on circumcision. Jerusalem accepted the view that circumcision was not necessary and Paul recognised the central position of Jerusalem for the faith. It also needed money. It was after then that Paul went out on a decade long series of missions (not before his Jerusalem visit, as wrongly stated in Luke's Acts of the Apostles), and this helped change the nature of the Church from being basically Jewish. Nevertheless, Paul was in dispute with Peter at Antioch when Peter refused to eat with non-Jews, a reflection of the situation in Jerusalem too. Paul on his travels was able to influence the new congregations according to accounts in Acts and Paul's own correspondence, his Epistles.

Paul first went to Cyprus, Asia Minor and Corinth, and finally Rome. Barnabus went with him at first to Cyprus, Perga, Iconium and Lystra, where Paul was stoned, but, along with the Peter dispute, Paul probably fell out with Barnabus over the Jewish observance issue. Paul stressed faith in the risen Christ over observance. They did argue over taking John Mark whom Paul distrusted as work shy. In the end Paul took Silus and Titus.

In the second journey the trip to Asia Minor (again) was extended to Macedonia because of a dream featuring the Holy Spirit. He went to Philippi and then Thessalonica. Orthodox Jews forced him to be smuggled out. He went to Beroa and faced opposition there and so continued on to Athens and finally Corinth where he stayed one and a half years from 50 to 51 CE. Some of the Jews were Christians but others ended his weekly trips into the synagogue and so Paul confined himself to houses.

Then he went to Ephesus and then Jerusalem (briefly). He took money to Jerusalem but in doing this had to prove his Jewishness to James. He went back to Antioch.

Then he went back to Asia Minor again and was attacked in Ephesus because of fellow Christians threatening the trade in Diana goddess statuettes. He went to Macedonia and Greece, but avoided Ephesus this time by going back via the islands of Mitylene, Chios, Samos, Cos and Rhodes. He landed at Tyre and went to Jerusalem.

Paul was received with hostility in Jerusalem but was rescued by the Romans. The locals were still after Paul, so the Romans using two hundred soldiers took him to Caesarea. The procurator Felix left him in prison for two years (58-60 CE) until the new procurator decided to send him to Jerusalem. Paul claimed his Roman citizenship for a trial in Rome, which fixed his destination even though King Herod Aggrippa II saw his interrogation and reckoned that he could even be set free. Seeing Paul's presentation of his defence, the king nearly converted to Christianity. The journey involved leaving Caesarea in a boat for Myra and Lycia (Asia Minor again), and from there in a boat to Italy. Here the story is dressed up a bit by whoever was the author: the boat reached Crete, drifted for fourteen days and was shipwrecked at Malta. From there Paul went to Malta and a formal welcome in Rome, and apparently given freedom to preach. There is no more in Acts despite this being the place of likely martyrdom.

Given who killed Jesus, Paul strangely thinks that the Roman authorities are servants of God and asks Roman Christians to obey the government (Romans 13: 1-7). He liked its stress on law and order (this contrasts with Revelation which regards Rome as satanic). He was, of course, a Roman citizen and expected to benefit from this badge but, beyond these texts, his luck ran out.

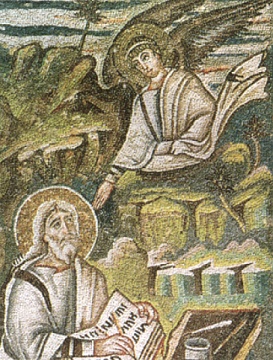

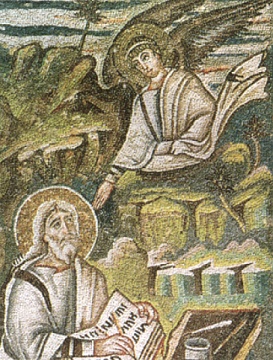

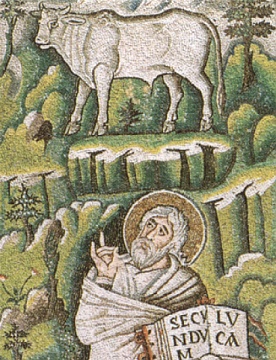

There is a Mark in 1 Peter and a John Mark in Acts but the Evangelist author is most likely another person. He may have inserted himself, in the form of cameo appearances, as a young man into the scene of Jesus' arrest fleeing naked and as the young man at the tomb. These are for literary effect to add to the existing literary effect of the stories and should definitely not be taken in a fundamentalist sense as he was not a reporter in the thick of the action. There is an association with Peter in tradition but this is unknown. Another tradition states that Mark founded the Church in Alexandria, Egypt, and was martyred there. Whoever else he was, he was almost certainly the first of the gospel writers, producing a narrative some forty years after Jesus death, working with the material at hand and the needs of the early Church expecting the coming of the Messiah and the (continued) beginning of the general resurrection. His text is more messianic than theological. The gospel reflects something of the devastation brought by the Romans to the Temple in 70 CE and the sense of the last days (like Paul): Jesus may still have worked within this eschatological viewpoint himself.

There is a Mark in 1 Peter and a John Mark in Acts but the Evangelist author is most likely another person. He may have inserted himself, in the form of cameo appearances, as a young man into the scene of Jesus' arrest fleeing naked and as the young man at the tomb. These are for literary effect to add to the existing literary effect of the stories and should definitely not be taken in a fundamentalist sense as he was not a reporter in the thick of the action. There is an association with Peter in tradition but this is unknown. Another tradition states that Mark founded the Church in Alexandria, Egypt, and was martyred there. Whoever else he was, he was almost certainly the first of the gospel writers, producing a narrative some forty years after Jesus death, working with the material at hand and the needs of the early Church expecting the coming of the Messiah and the (continued) beginning of the general resurrection. His text is more messianic than theological. The gospel reflects something of the devastation brought by the Romans to the Temple in 70 CE and the sense of the last days (like Paul): Jesus may still have worked within this eschatological viewpoint himself.

Mark's emphasis is the crucifixion as a saving event and the resurrection of Christ as the way ahead to coming events. Put before this chronological narrative is a rather selective and less than chronological series of teachings, preachings and miracles of Jesus leading up to events that brought about his arrest. The whole of Mark's gospel is not a history but a straightforward future orientated statement of faith.

Mark is not interested in Jesus' genealogy but is keen to point out that by his words, works and events that Jesus was a unique suffering servant making the difference for the future. Of the three synoptic authors, he comes closest to saying Jesus is divine (this does not mean that Jesus did, nor that it carries the same meaning as is commonly given). Jesus is transformed and is able to speak with (and therefore is associated with and supersedes) Moses and Elijah - with Peter, James and John listening. The action is centred in Galilee until the final journey south and Galilee is the place where the risen Jesus will be found.

One underlying issue for Mark is why only a minority of Jews have seen that the Messiah has come, and have continued to go to synagogue still waiting. He decides that God must in some way be deliberately concealing his revelation, and he sees the explanation in the method of the parable. Whereas for Jesus the parable was to plug into everyday experience and make complex matters realised, for Mark the opposite is the case. They have been given with the intention of holding something back and adding to the mystery, as indeed he is puzzled. The Parable of the Sower (Mark 4: 1-20) is a key parable to the rest about those who respond and those who do not respond to Jesus. Mark still uses parables to explain, but as he struggles for the meaning given the time and place shift from Jesus to Mark, so he expects obscurity to be part of the means of explaining and concealing. Thus the reader is privileged with the extent of explanations Mark adds, and of course the Messianic figure knows what he is saying and doing, but others show their puzzlement and astonishment for whom additional explanation never came.

At the focus of the suffering and then resurrection, the disciples are puzzled when he is alive and have been failures when he died. Once again the reader is privileged to know the remarkable nature of Jesus while these characters within are astonished. This puzzlement is the driving narrative that glues together the various nuggets of information throughout the Gospel that Mark had to work with. Mark was writing for those who already knew the kerygma as they had received it, so that insiders are let in on the secret and this yarn is about the astonishment Jesus generated amongst others. It adds to and affirms the insiders' joy and assuredness. Anyone who read this who did not know the story (that is, converts) would be in the same place as the impressed characters who meet Jesus, though everyone is let in to the denouement before the action gets going.

The Markian essential is:

- Jesus is greater than John the Baptist

- He resisted temptation

- He fulfils Hebrew Bible prophesies

- Jesus had to suffer

- He pleases God

- He has divinity

- Jesus is the Messiah

- The Holy Spirit is upon him

- He will baptise others with the Holy Spirit

A central message then is the Son of Man must suffer and the coming of the Son of Man out of the clouds in glory before the generation passes away. To some extent there is an imposing of divine status on to Jesus that Jesus himself may not have made, though Jesus may have come to realise his specialness under God and a key role in bringing about the last days. The context is certainly that the last day is close, though Mark wrote at a time of intense stress about the present and future.

Unlike for Paul, there is a chronological style narrative for the suffering and resurrection. A question is whether Mark invented the empty tomb story (the women, themselves lesser reliable witnesses, told to say nothing, suggesting why the empty tomb was unknown before in early church community). Here though is the requirement for the criticised disciples to carry on the work.

The short gospel leaves many questions open, where faith is centred and expectant. Its original abrupt end led to an ending being attached, and to other gospel writers answering the unfinished parts their ways.

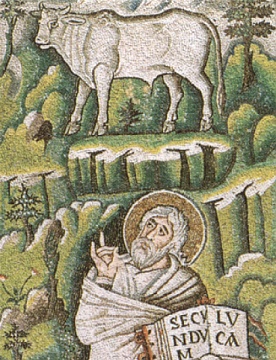

This Matthew is not the Matthew in the gospels. This one is likely a Syrian Jew who spoke Greek whose name is unknown. He wrote around 75 to 85 CE. Ninety per cent of Matthew is from Mark (600 of 660 verses), but Matthew wanted Mark neater and more complete. He put two genealogies to the front (Jesus the descendant of David and of a mistranslated young woman into virgin) and made the resurrection less of a mystery with glossed in and changed details. He tells of what happens in Galilee.

This Matthew is not the Matthew in the gospels. This one is likely a Syrian Jew who spoke Greek whose name is unknown. He wrote around 75 to 85 CE. Ninety per cent of Matthew is from Mark (600 of 660 verses), but Matthew wanted Mark neater and more complete. He put two genealogies to the front (Jesus the descendant of David and of a mistranslated young woman into virgin) and made the resurrection less of a mystery with glossed in and changed details. He tells of what happens in Galilee.

Matthew claims that Jesus was in the line of David and therefore legitimately the Jewish Messiah. Jesus is the true Israel. It goes past the Babylonian Exile and right back to Abraham no less. This conflicts with Mary as a virgin, though here was a mistranslation. The place of the birth narratives is to add significance to this person. However, Jesus is certainly fully human. The Old Testament had made predictions, and Jesus fulfilled them (for example, a birth in Bethlehem matches the Hebrew Bible location given that it was the city of David, and there was the unhistorical slaughter of infants and flight to Egypt just to meet Hosea 11: 1). Expectations are important, again tied in to the sweep of historical narrative.

As for earthly events, some have a reconstruction for the purpose of clarity but also biblical parallel. The Sermon on the Mount is not one sermon but a gathering of rabbinical sayings from Jesus that tell something of the demand of the New Age coming with immediacy and making its idealistic demand now. The mount is a parallel with Moses, with the twist that Jesus delivers his beatitudes from the mountain to the disciples whereas Moses came off the mountain to hand over the Law. Jesus can thus be understood as higher than the disciples, that they like Moses are simply receiving the truth to hand it on.

Yet, more than a few times, Jesus' ministry is arranged to tie him into the Hebrew Bible with historical continuity. When Jesus is in the wilderness tempted by the devil (Matthew 4: 1-11), the test is not particularly about his psychological state but his relationship to Israel. Jesus' three replies to the devil are scriptural quotations when Israel was tested and failed (Deuteronomy 6: 13, 6: 16, 8: 3). In contrast, Jesus, the supreme Israel, succeeds in his obedience to God.

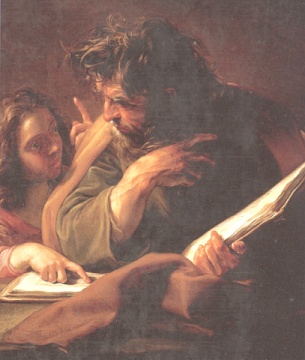

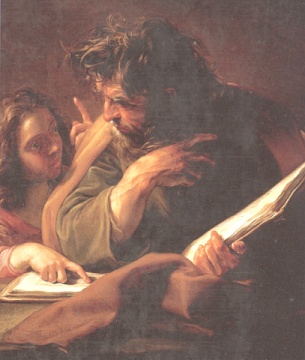

He wrote a gospel after 80 CE (50 years after Jesus' death) and its sequel, Acts (see Peter). Acts describes the early Church and its mission, with a strong focus on Paul and less on Peter. Peter material may come from Aramaic early Jerusalem church sources (Aramaic was the language of Jesus and there are Aramaic sources for Jesus' sayings). It is doubtful that this Luke accompanied Paul on his missionary journeys and stay in Rome, and so this material probably was not direct.

He wrote a gospel after 80 CE (50 years after Jesus' death) and its sequel, Acts (see Peter). Acts describes the early Church and its mission, with a strong focus on Paul and less on Peter. Peter material may come from Aramaic early Jerusalem church sources (Aramaic was the language of Jesus and there are Aramaic sources for Jesus' sayings). It is doubtful that this Luke accompanied Paul on his missionary journeys and stay in Rome, and so this material probably was not direct.

Acts contains both an emphasis on the preaching of the Kingdom of God and Paul's preaching of Christ. This is for all nations.

About fifty per cent (350 of the 660 verses) of Mark effectively constitutes Luke's gospel. Much is added however, for example the birth and early life of John the Baptist, Jesus going into the Temple early on, and some significant parables (Good Samaritan, Prodigal Son, Lazarus as the rich man in hell). The place of the first resurrection appearance to direct the disciples is moved to Jerusalem. An emphasis is on Jesus as Lord anointed by God.

Luke's style is not like Matthew (to show prophecy fulfilled by quoting the scriptural texts) but uses words and phrases to bring forth the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible, and thus he was continuing it. It is a literary style, for example in the interweaving of John the Baptist's and Jesus' early life often in words attributed to others using verse with added commentary.

Differences also include the Sermon on the Plain (Luke 6: 17-49) where lkike Moses Jesus goes to the hills to pray and returns to the foot of them to teach. Both Luke and Matthew are theological, but create different dramas even from similar material and intentions. Luke's sermon is more balanced than Matthew's, with woes as well as beatitudes, and they are more material but with a reversal of what God considers important.

The poor and ordinary are rated above the religious specialists, who often fail to see the significance of Jesus' flexibility. Luke has the woman who anoints Jesus with perfume (Luke 7: 36-50) (his feet, like John; Mark and Matthew use the head) as a sinner who repents and honours Jesus unlike the Pharisee who cannot even be courteous.

The Good Samaritan story appears in Luke only (Luke 10: 25-37), where the concept of neighbour is extended beyond all realised limits. Again religious leaders are criticised for their narrowness even to the extent that what looks like the pollution of a corpse prevented their worship in the Temple. Another included outsider was Zacchaeus (Luke 19: 1-10), a chief tax collector who demonstrates repentance and so is another lost person restored.

There is an interesting puzzle over whether there is a second cup in the Last Supper or not (Luke 22: 15-17). If a second cup was added as in some manuscripts then this is for liturgical conformity with the other Gospels. If one cup is the original, then it suggests liturgical diversity at the time of Luke. For the actions in the Last Supper come not from an historical record, as such in the detail, but from the practices in the early churches.

Luke is understood to be a physician and saint. He was a Greek Gentile, probably from Antioch, and a high level writer.

The John who wrote the gospels may have written the Johannine epistles too, but he did not write the Book of Revelation.

This John may have lived to old age in Ephesus.

The John of the Book of Revelation is said to have received his message from an angel. He went to Patmos in the Dodecanese.

Whilst this gospel tells of what Jesus did and said and then centres on the crucifixion and resurrection, it includes Jesus' apparent earthly activity in Jerusalem. The cleansing of the Temple comes early in Jesus' ministry (John 2: 13-22) rather than at the end, as with the synoptics, this time to be a sign towards Jesus' death and resurrection and a change in worship: the temple of his body destroyed and raised in three days. There is no transfiguration, no Last Supper and no expression in the Garden of Gethsemane. The crucifixion is moved forward one day. The expectant eschatology is replaced by a Hellenistic mysticism of Christ, far more deeply than that of Paul's change.

Whilst this gospel tells of what Jesus did and said and then centres on the crucifixion and resurrection, it includes Jesus' apparent earthly activity in Jerusalem. The cleansing of the Temple comes early in Jesus' ministry (John 2: 13-22) rather than at the end, as with the synoptics, this time to be a sign towards Jesus' death and resurrection and a change in worship: the temple of his body destroyed and raised in three days. There is no transfiguration, no Last Supper and no expression in the Garden of Gethsemane. The crucifixion is moved forward one day. The expectant eschatology is replaced by a Hellenistic mysticism of Christ, far more deeply than that of Paul's change.

This gospel is more deeply theological and explanatory than the first three, so that a cosmic plan is at work. The authorial interpretation is made obvious. Jesus Christ is integral to creation, and is from before the worldly beginning as well as to the culmination. So the beginning is not John the Baptist, or stories of the birth, but the start of time with a nod towards Genesis. In this gospel Jesus believes in his own divinity, and is superior to all that is before, whereas other gospels give a more qualified and developmental view of his own self understanding. Jewish and Greek ideas are built in.

Whereas the synoptic gospels can be dug into to find something of a biography of Jesus, but this is fairly impossible with John. The words are imposed on to Jesus from a theological distance. John may preserve some early traditions, but he does not preserve a biography. Jesus does not fit into his own historical context: he did not speak and think as portrayed. John put on to Jesus what people around him generations later had come to think. Jesus did not think he had come from heaven and taught his own exalted status of which he was fully aware. He did not remember being with God. There is no development. And surely the writers of the synoptic gospels if they had this information would not have suppressed it and therefore this gospel is out of keeping and not theirs.

Simon, nicknamed Peter (Cephas) by Jesus, was so nicknamed to represent the word rock. He was married.

Peter is the leading apostle among the disciples. It is interesting that all the time he is raised up in status, checks are made that keeps him below Jesus. The emphasis for the early community, therefore, was that although Peter was very important, and he could perform miracles, he never achieved Jesus' status. He was the first person to say to Jesus that he was the Christ. Yet he denied Jesus three times in the Temple with an emphasis of forgiveness on him afterwards. Peter tried to walk on water (unlike others) in the manner of Jesus, but could not. With James and John, the sons of Zebedee, Peter was within the chosen few within the disciples. Only Peter, John and James saw the transfiguration. These three accompanied Jesus when Jairus' daughter was brought back to life. Peter and John are given as the two who went to get the colt and the ass for Passover and they went with Jesus furthest into the Garden of Gethsemene. John arrived first at the empty tomb and Peter went inside, says John (and some manuscripts of Luke have him visiting at 24: 12). Peter and John too were at the forefront of early Church movement, and Peter acted with authority at Pentecost. He went on missions to Judaea and Syria.

Peter is the leading apostle among the disciples. It is interesting that all the time he is raised up in status, checks are made that keeps him below Jesus. The emphasis for the early community, therefore, was that although Peter was very important, and he could perform miracles, he never achieved Jesus' status. He was the first person to say to Jesus that he was the Christ. Yet he denied Jesus three times in the Temple with an emphasis of forgiveness on him afterwards. Peter tried to walk on water (unlike others) in the manner of Jesus, but could not. With James and John, the sons of Zebedee, Peter was within the chosen few within the disciples. Only Peter, John and James saw the transfiguration. These three accompanied Jesus when Jairus' daughter was brought back to life. Peter and John are given as the two who went to get the colt and the ass for Passover and they went with Jesus furthest into the Garden of Gethsemene. John arrived first at the empty tomb and Peter went inside, says John (and some manuscripts of Luke have him visiting at 24: 12). Peter and John too were at the forefront of early Church movement, and Peter acted with authority at Pentecost. He went on missions to Judaea and Syria.

There are two Epistles in his name but the second comes from Egypt in the 100s CE. The first is not likely his either. There is an Acts of Peter not part of the canon, where Peter meets Jesus outside of Rome. Peter asks Jesus where he is going - Quo Vadis? - and Jesus says to be crucified again. There is no narrative descriptive account of an appearance to Peter in the gospels. However, Peter, receiving an appearance according to Luke (Luke 24: 34) and Paul (1 Corinthians 15: 5), is featured with importance in Acts.

This was the basic message of Peter, according to his speeches in Acts:

- The age of fulfilment foretold by the prophets has come and this is the time of the Messiah

- The fulfilment is through the ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus

- It happened with the plan and foreknowledge of God

- The works, wonders and signs were done by God through Jesus of Nazareth

- Moses said there would be another prophet like him who should be listened to in everything regarding his preaching

- People denied the Holy and Righteous One and killed the Prince of Life

- God raised him up and the community comprises witnesses

- God raised him from the lawless men who had crucified and killed him

- The resurrection meant Jesus became the Messiah exalted at the right hand of God (Psalm 110)

- God made him Lord and Christ

- God glorified His Servant Jesus

- The Stone rejected by the builders has become the head of the corner (Psalm 118: 22)

- God had sworn that one of David's descendants would rule

- This is as Israel, the offspring of Abraham

- God exalted him to give repentance to Israel, and remission of sins

- Everyone who believes in him shall receive remission of sins through His name

- The exalted one received the Holy Spirit and visibly and audibly pours this out (Joel 2:28-9) to the obedient witnesses.

- There is a need for repentance: forgiveness will follow due to the outpouring Holy Spirit and there will be salvation in the New Age

- The Messianic Age results in the return of Christ to judge the living and dead

There is a difference between Peter (Jerusalem) and Paul:

- Jesus as Son of God but rather is the Servant of God in Deutero-Isaiah fashion, that is messianic rather than theological (Acts says Paul first used Son of God, and this is in the Synoptic Gospels)

- Christ did not die for our sins but the product of the life, death, and resurrection of Christ is the forgiveness of sins (though Isaiah, important to the Jerusalem church, has the Suffering Servant approach, and this is more than Pauline alone)

- The exalted Christ does not directly intercede (in the Matthew he does, so the idea is more than Pauline alone)

There is agreement with:

- David's line

- Death according to the Scriptures

- Resurrection according to the Scriptures

- Exaltation

- He takes people from sin to new life

- His return for the New Age

Peter was the leader on the ground but lacked the ideological reach of Paul.

Basically, Peter agreed with Paul's emphasis on admitting Gentiles and in fact baptised the first Gentile convert, Cornelius. Still, he was circumspect among conservative Jews counted as Christians, and without Paul the movement would have been more Jewish.

John was executed by Herod Agrippa I but the story goes that Peter, arrested at this time, was rescued by an angel. Nevertheless Peter was martyred in Rome by being crucified upside down after the Great Fire in 64 CE, probably when Paul met his end as well. Some say the tomb under St. Peter's in Rome is indeed his.

Adrian Worsfold

Used in part:

Calvocoressi, P. (1999), Who's Who in the Bible, new illustrated edition, London: Penguin Reference Books.

A strange book especially for an historian in that it lifts biographies off the page and haphazardly gives insights into biblical criticism with no consistency.

Hooker, M. D. (1979), Studying the New Testament, London: Epworth Press.

A book for Methodist trainee Lay Preachers making its style accessible but substantive. It assumes faithful belief in offering the general results of scholarship.

Adrian Worsfold

He was called Saul until conversion and lived from 1 to 64 CE. He was born a Jew in Greek Tarsus and died in Rome probably as a result of Nero's persecution which followed the Great Fire of that year. He followed the Pharisees and in so doing took on Christian Jews who were light about the Law. Some two years after Jesus' death he experienced a conversion on the Damascus road, about which as well as the obvious explanation of receiving an appearance there are many psychological theories relating to his self guilt and even a suggestion of electrical activity in the earth from a far off earthquake.

He was called Saul until conversion and lived from 1 to 64 CE. He was born a Jew in Greek Tarsus and died in Rome probably as a result of Nero's persecution which followed the Great Fire of that year. He followed the Pharisees and in so doing took on Christian Jews who were light about the Law. Some two years after Jesus' death he experienced a conversion on the Damascus road, about which as well as the obvious explanation of receiving an appearance there are many psychological theories relating to his self guilt and even a suggestion of electrical activity in the earth from a far off earthquake. There is a Mark in 1 Peter and a John Mark in Acts but the Evangelist author is most likely another person. He may have inserted himself, in the form of cameo appearances, as a young man into the scene of Jesus' arrest fleeing naked and as the young man at the tomb. These are for literary effect to add to the existing literary effect of the stories and should definitely not be taken in a fundamentalist sense as he was not a reporter in the thick of the action. There is an association with

There is a Mark in 1 Peter and a John Mark in Acts but the Evangelist author is most likely another person. He may have inserted himself, in the form of cameo appearances, as a young man into the scene of Jesus' arrest fleeing naked and as the young man at the tomb. These are for literary effect to add to the existing literary effect of the stories and should definitely not be taken in a fundamentalist sense as he was not a reporter in the thick of the action. There is an association with  This Matthew is not the Matthew in the gospels. This one is likely a Syrian Jew who spoke Greek whose name is unknown. He wrote around 75 to 85 CE. Ninety per cent of Matthew is from

This Matthew is not the Matthew in the gospels. This one is likely a Syrian Jew who spoke Greek whose name is unknown. He wrote around 75 to 85 CE. Ninety per cent of Matthew is from  He wrote a gospel after 80 CE (50 years after Jesus' death) and its sequel, Acts (see

He wrote a gospel after 80 CE (50 years after Jesus' death) and its sequel, Acts (see  Whilst this gospel tells of what Jesus did and said and then centres on the crucifixion and resurrection, it includes Jesus' apparent earthly activity in Jerusalem. The cleansing of the Temple comes early in Jesus' ministry (John 2: 13-22) rather than at the end, as with the synoptics, this time to be a sign towards Jesus' death and resurrection and a change in worship: the temple of his body destroyed and raised in three days. There is no transfiguration, no Last Supper and no expression in the Garden of Gethsemane. The crucifixion is moved forward one day. The expectant eschatology is replaced by a Hellenistic mysticism of Christ, far more deeply than that of Paul's change.

Whilst this gospel tells of what Jesus did and said and then centres on the crucifixion and resurrection, it includes Jesus' apparent earthly activity in Jerusalem. The cleansing of the Temple comes early in Jesus' ministry (John 2: 13-22) rather than at the end, as with the synoptics, this time to be a sign towards Jesus' death and resurrection and a change in worship: the temple of his body destroyed and raised in three days. There is no transfiguration, no Last Supper and no expression in the Garden of Gethsemane. The crucifixion is moved forward one day. The expectant eschatology is replaced by a Hellenistic mysticism of Christ, far more deeply than that of Paul's change. Peter is the leading apostle among the disciples. It is interesting that all the time he is raised up in status, checks are made that keeps him below Jesus. The emphasis for the early community, therefore, was that although Peter was very important, and he could perform miracles, he never achieved Jesus' status. He was the first person to say to Jesus that he was the Christ. Yet he denied Jesus three times in the Temple with an emphasis of forgiveness on him afterwards. Peter tried to walk on water (unlike others) in the manner of Jesus, but could not. With James and John, the sons of Zebedee, Peter was within the chosen few within the disciples. Only Peter, John and James saw the transfiguration. These three accompanied Jesus when Jairus' daughter was brought back to life. Peter and John are given as the two who went to get the colt and the ass for Passover and they went with Jesus furthest into the Garden of Gethsemene. John arrived first at the empty tomb and Peter went inside, says John (and some manuscripts of Luke have him visiting at 24: 12). Peter and John too were at the forefront of early Church movement, and Peter acted with authority at Pentecost. He went on missions to Judaea and Syria.

Peter is the leading apostle among the disciples. It is interesting that all the time he is raised up in status, checks are made that keeps him below Jesus. The emphasis for the early community, therefore, was that although Peter was very important, and he could perform miracles, he never achieved Jesus' status. He was the first person to say to Jesus that he was the Christ. Yet he denied Jesus three times in the Temple with an emphasis of forgiveness on him afterwards. Peter tried to walk on water (unlike others) in the manner of Jesus, but could not. With James and John, the sons of Zebedee, Peter was within the chosen few within the disciples. Only Peter, John and James saw the transfiguration. These three accompanied Jesus when Jairus' daughter was brought back to life. Peter and John are given as the two who went to get the colt and the ass for Passover and they went with Jesus furthest into the Garden of Gethsemene. John arrived first at the empty tomb and Peter went inside, says John (and some manuscripts of Luke have him visiting at 24: 12). Peter and John too were at the forefront of early Church movement, and Peter acted with authority at Pentecost. He went on missions to Judaea and Syria.