The impression of authenticity of the gospels is that they come from the centre of early Christianity outwards to the faithful. I think they are examples of decentred writing: multiple sourced, already spread out, already serving confessional purposes, and weaved into narrative appearances:

- Mark as who was Jesus and why suffer?

- Matthew as Jewish connections and Israel's failure

- Luke as the poetic and then the appearance of history for the empire

- John as signs located in Palestine and replacing Judaism

|

|

No one wrote history when cataclysmic events were still due to take place. No one wrote history afterwards. Writing first of all was for mundane communication, in which Paul and support reasoned his belief to communities. Later writing in the gospels was to frame and give purpose; to reflect and sometimes to guide.

|

|

Mark's gospel comes after the death of Paul and Peter. There is a need to write things down now, because of the level of persecution under Nero. People are dying and memories are being lost; people need to relate their suffering with the originator's and gain strength. So it is largely a narrative of the passion (especially 8:31 on). We suffer as Christ suffered, it says. It asks who is Jesus and in the process proclaims Jesus as Messiah in the attempts to answer why the Messiah suffered death. Mark the author is an unknown. One possibility only is it's John Mark, a friend of Peter and sometimes occasional sidekick of Paul. It is not refined literary writing, and is happily imprecise about dates and times. It is some 35 plus years after Jesus' death. The end of it (after "for they were afraid") is likely second century in addition.

|

|

|

Matthew draws on Mark (about 50%). The author of Matthew is unknown. Matthew draws on sayings from Q; Matthew has his own incidents and teachings called M. Matthew likes his numbers: his threes, fives and sevens and an important twelve for arranging things. It is about prophecy, order, connections, lineages. It is Jewish: Jesus follows on from Moses, and he and his disciples were very faithful to the Law because they also followed its spirit, and this against opposition and the failure of Israel to recognise the Messiah and therefore the need to spread out geographically from the original intention. A writing location of Antioch, Syria, is probable.

|

|

|

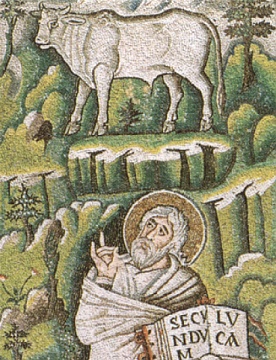

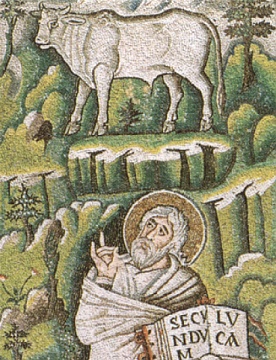

Luke likes order too. It begins with poem-like material including birth narratives of Greek writing from Jewish sources, but from Chapter 3 it is set out like history (unlike Mark and Matthew). It is thoroughly Gentile ("a light to lighten the Gentiles..."), respectable and recommending itself to the Romans. He plonks in Mark almost in isolation and his own material seems separated. There is Q with Matthew. There is material of sayings from Palestine when Paul was imprisoned. Luke might have sailed with Paul, receiving information third hand or more if he did. Luke's own material, L, is from his own travels in Caesarea and Jerusalem among believers. Some passion material is not from Mark even though Mark is used. Luke continued on into Acts, which often does not agree with Paul but provides comparative and additional material. It emphasises the importance of going out to the Gentiles, a true path of continuous activity of God beginning with the Hebrew Bible and now through Christ. This writing is many years after apparent events, and sees them through a later perspective.

|

|

|

These are the synoptic (seen together) gospels. They have core material but they are not primary source historical documents as we understand the concept. If the history side is forced, they fail. The history has to be teased out by close methods.

|

|

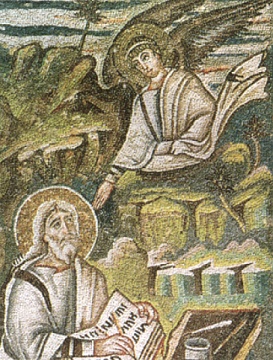

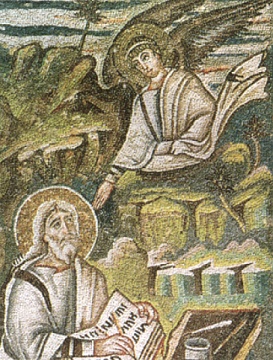

John is symbolism, a theological exposition, where the narrative of supernatural signs goes in for geographical and timing detail to root its overall purpose. This purpose is the replacement of the old Judaism. The author is anonymous. Other biblical material has the same author's name, but the authors are quite different (whereas Luke and Acts have the same author).

|

|